Wordless

Andreas Slominski: Sometimes I think that practically any word about his work is a word too many. And yet it’s hard to resist the temptation to talk about it. When the objects are as literal as these and when the artist fades wordlessly and almost ostentatiously into the woodwork, the desire to tell stories automatically arises. His objects and deeds inevitably provoke eloquent description and poetically attuned commentary. Where the works suggest an artistically laconic retreat to a terrain that has yet to be discovered, the interpreting viewer resorts to an arsenal of elaborate equipment. And in the final analysis, extensive accounts of the circumstances may even serve to allay the suspicion of a certain affinity with Till Eulenspiegel.[1]

There is also a certain rightness about this predilection for words, this tendency towards a verbal elaboration of the artist’s pictorial gestures, because, in addition to being so literal, each of the works makes an imperfectly concealed expressive impact that could serve as a springboard for reflection beyond the givens of these gestures. The little stacks of dust cloths, so fresh and carefully folded, have a density that inspires thoughts as much about fragile emotions as about sculpture. Or is it mere coincidence that the melancholy elegance of the giraffe bending its neck to lick the stamp calls to mind the streetlamp in the same city with a bicycle tire wrapped around it? And in a large exhibition of traps, why are we suddenly so certain that we are in the midst of a landscape painting? Even the most mundane object used as the vehicle of action in the artist's scenes (like the wooden ice-cream stick in the department store window) effortlessly speaks such a distinct language. Even before we learn anything about the circumstances of its appearance, it has already made an impression. Its form possibly combined with only a vague idea of its function is enough to conjure up a mood that could pave the way to meaning. But the word that may seem to emanate from the object is merely an insinuation; it is too short and too understated or odd to count as speech. But it acts as a stimulus to complement it with narrative.

And then there are the circumstances behind the objects! Sometimes the artist discloses them in photographs and films. But even when he doesn’t, he sees to it that the stories get around—one way or another. And having leaked out, they instantly become inseparably intertwined with the objects. In one case, Slominski centerstaged the story itself by circulating the rumor that a human hand had been concealed in the wall of an empty room. Should we perhaps focus our attention entirely on the back- ground of the things we encounter on site? Would it make sense to treat the object only as a catalyst, whose meaning takes shape in the striking clarity or enigmatic mystery of the story? And would the artist then have set up his traps in the space of the imagination created by the reports of what he does, rather than in visible space? That would certainly be a possibility. It would be most appropriate, for then he would simply posit points of departure as trajectories for the actual works, which would develop in the form of a more or less open discourse or a chain of actions. Instead of overwhelming or displacing the objects, these stories and accounts would, in fact, be their justification.

Or is it a giraffe of an entirely different color? Perhaps the stories and speculations are simply the murmur and susurrus that ensues when the thing itself yields only what it must and nothing more. The rush of words would then be the attempt to lessen the shock caused by the speechlessness of the works. The lack of language is related to the suddenness with which the works accost us. The essence of the experience lies in those first seconds when we enter the museum space and unexpectedly come upon the old, twisted bicycle. Or in that split second when the familiar and innocent thing at our feet shoots the words “trap” and “snap shut” into our brains. But also when the eternal tranquillity of the pile of dust cloths abruptly cuts into and affectively cuts through our detachment. Later then, we might join in an investigation that exposes details, and thus seek to fix the experience. That is neither wrong nor useless but, as a posterior act, it will never equal the first – and probably irrevocable – moment. Think of a successful poem in which two or three words meet up with each other in a way that is utterly incredible, utterly unheard of – and instantly makes compelling sense. Even here, where the material consists of language, words fail and pure chemistry is at work. The artist’s objects and actions come from this side of language. They are pure images that make no claim to achieving speech. Their moment is the wink of an eye—mute, but intense and clear. Andreas Slominski: word-less.

[1] Legendary German practical joker, similar to Punch.

Translated from the German by Catherine Schelbert

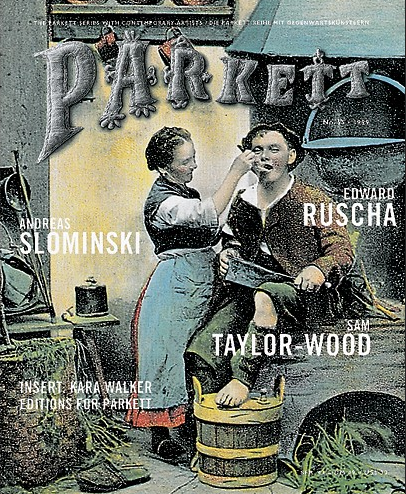

(Published in: Parkett, No. 55, Juni 1999, pp. 94-95 (German), 96-97 (English))