My first visit to Franz West’s studio in Vienna was probably in the winter of 1986. On the way he insisted on taking the underground for one particular stretch of the journey, probably between Stadtpark and Kettenbrückengasse. His purpose was to draw attention to certain ducts on the walls of the tunnel. What slipped past the windows left only a fleeting impression, but for Franz it was an important clue. In the studio, I found that he had transcribed this impression into a relief titled Vedute (Views). The long-drawn-out second of that glance in the murky underground (an everyday and yet mesmerising banality) had mutated into a proud overview: an underground Canaletto – this is what the title seemed to suggest. The following year, the relief was enthroned in the serene expanse of a house by Mies van der Rohe as part of an exhibition entitled Anderer Leute Kunst (Other People’s Art).

Before or after the visit to the studio, a rather tattered paperback appeared from the artist’s coat pocket. Some of the pages were dog-eared where he’d turned the corners down as a reminder. He flicked through and read a sentence or two, or even just half sentences, but he knew exactly which thoughts he wanted to share. It was almost impossible to understand at first. Only the title of the book was straightforward: Gesture and Speech, by the palaeontologist and anthropologist André Leroi-Gourhan.

On another occasion things ran late during the installation of an exhibition at the Museum Haus Lange in 1989. The works had arrived late – or maybe Franz himself was late – and the pedestals for his chairs still had to be painted (it’s better to do this kind of thing yourself when time is pressing). Meanwhile there was a lot of talk about this and that, also about the then new seats, which you had to go up onto the plinth to use. The hands that painted the pedestals and the words that seemed necessary to understand something of the work became, at some point, indistinguishable. By this time it was getting late, the pedestals were ready for the slanted furniture show. Had the thoughts now disappeared into the paint, or did the paint speak of the thoughts? For a while such a merging of categories seemed to be possible. At the opening, everything was real: the people on the seats, talking, pondering, facing the wall or looking out of the windows. Rüdiger Carl provided some short pieces of music.

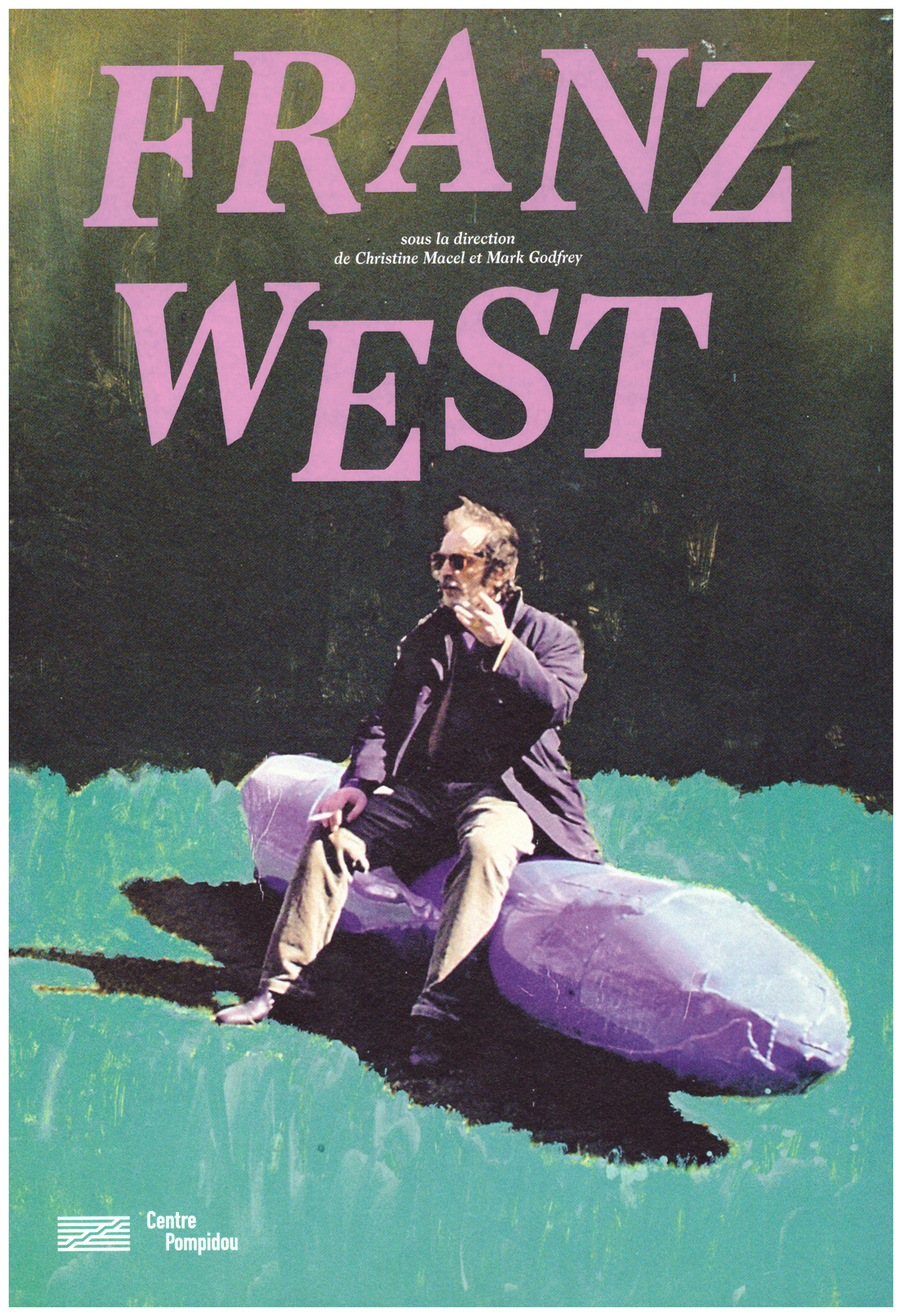

(Published in: Franz West, Centre Pompidou, Paris, 2018, p. 106 (French), and Tate Modern, London, 2019, p. 106 (English))