Doing Nothing As A Chance To . . .

Just sitting there and looking out at the lake is also an end in itself. Just gazing at a tree, in peace, can be a real necessity. You can forever be looking at pictures that shout at you or make you nervous.

T. S.

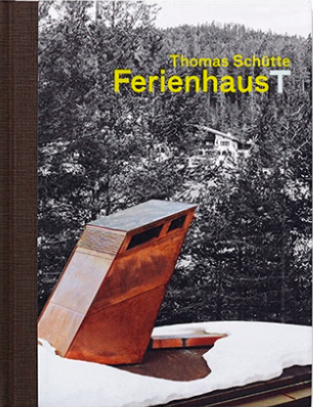

Not visible from the road, a cliff face rising up behind it, conifers all around and in close proximity. As you ascend the steep path it slowly appears up ahead; turn left and you find yourself on a little plateau, a terrace, facing one of the short sides. Walking along the side of the house you come to four simple steps and a door, barely visible in the glass wall that runs right round the house. You have arrived at Ferienhaus T. Some houses bear the name of their maker or indicate their location in some way; sometimes poetic words express an implicit desire or a fantasy. Things seem rather more prosaic here. T could stand for Tirol, because that is the name of the Austrian region where it has been built. Except that this house has a particular past, or to be more precise, it was preceded by a model, several models. Nine years before it was constructed Thomas Schütte created a series of models of holiday homes for terrorists—Ferienhäusern für Terroristen—on a scale of 1:20. Of course it is reasonable to wonder whether the title is ironic or a serious recommendation to terrorists. Haven’t we repeatedly heard how important hideaways are to “freedom fighters”? But which terrorists are we thinking about here? The usual, politically motivated underground fighters or perhaps a rather different (albeit, passé) vanguard? The rigorous primary colors of the Plexiglas walls and the somehow futurist forms of the model houses might appear to be a sarcastic dismissal of the will to power of all-pervading modernism: a sideswipe at aesthetic mind-terrorists, who believe that there is only one acceptable décor for modern life. But these questions don’t have to be resolved. The summary models from 2002 are not all we have. Four or five years later Schütte made another two models—from metal, this time, and more detailed. On a scale of 1:10, these are kitted out with doll’s-house furniture, even down to a fire extinguisher. And inside the model there is a translucent silhouette of a human being. A schematic occupant? A further two years pass, and now it is possible to walk around in yet another model. The scale has increased to 1:1—things could be getting serious. And suddenly a client makes contact, undaunted either by the ominous reference to “Terrorists” in the title or by the fact that the architect is an artist. He even has a plot of land—in the Tirol—in a famous holiday area.

More than perhaps any other artist of his day, Schütte has always included models (architectural models, that is) in his repertoire of artistic forms. However, these simply constructed, sometimes even improvised “images” are not models in the usual sense: they are not guides for making another, larger structure. On the contrary, they make an impact of their own by dint of their idiosyncratic capacity to induce mental and emotional responses in the viewer. They operate in a world of “as ifs”—like images expressed in three-dimensional subjunctive clauses. They tell stories and prompt other unpredictable and uncontrollable stories. It all started with a failed attempt to erect a functioning, full-scale construction, which then prompted the artist to make a model instead; this not only represented the original idea, it also became a work of art in its own right. The matter of the realizability of other works of this kind is if anything of secondary importance—not unlike a “what-if” thought, which can markedly increase the drama of some topics. Witness his model bunkers or, in a more idyllic mode, diverse artist’s studios and houses. The multiplicity of models and themes that have come about in parallel to the other main strand of Schütte’s work—his figurative sculptures—are unburdened by questions regarding their potential utilization; yet they do very effectively stimulate open-ended, pictorial thought processes.

The liberties and targeted imponderables of the subjunctive mood suggested by the model could—not least with respect to the artist himself—naturally also induce a sense of insufficient involvement or contact with life. As long ago as documenta in 1987, Schütte already set a temporary test of that kind, in the shape of a bar standing on its own in a park. Subsequently, since 2003 his various, increasingly detailed One Man Houses (most recently on a scale of 1:1) have seen him enter the realms of real architecture. And it is worth noting that this was the outcome of a set of fortunate circumstances as opposed to the conclusion of a carefully planned strategy. In short, this development was not instigated by a commission for a house but ensued from stimulus provided by a work of art in the form of a model. However, this transition into the business of designing and building has not turned the artist into an architect in the usual sense of the word. He himself, playing down what he does, refers to it as a hobby, and, as the provider of images and giver of ideas, he does not seek the limelight and only intervenes in the wider picture if necessary. In fact Schütte has never really had a studio of his own. When he was not making drawings and watercolors, or modeling small figurines “at his kitchen table,” he has generally sought out professional craftsmen in their workshops and has developed his works in close collaboration with these experts. Understandably, that applies all the more so in the case of the “real” houses. Wide-ranging assistance from architects, engineers, technicians, and craftsmen—not to mention the clients commissioning the houses—is indispensible. However, all these players are not just instruments used to fulfill the artist’s intentions, they are his collaborators—and they are as welcome as they are necessary. In the case of an object such as Ferienhaus T they are numerous and ultimately the finished article conveys an overall impression of being the culmination of the many and varied suggestions and decisions made by all these players. We see a finely calibrated ability to delegate at work here, which balances the artist’s visions-nightmares-inventions and his desire for the work also to be grounded in reality. To cite just one example: How was the outer skin of Ferienhaus T to be realized, considering that it looks like giant panes of colored glass in the model? It turned out to be impossible to produce colored triple glazing in these sizes, for technical, financial, and practical reasons. And an experiment with colored plastic looked exactly as one might expect—like a cheap substitute. The solution was to use colored drapes, with white drapes in places that could also be drawn as required or as befitted the mood. The idea for this solution came from the client, as did the suggestion to finish the base of the house and edge of roof in copper.

Nine steps from the entrance to the seating area, seven steps from the open fire to the bed, eight steps from the bed to the kitchen, sixteen steps from the bed to the bath, and twenty-four steps take you right through the house from the dining area to the toilet. It has the dimensions of any medium-sized, one-storey house. But these distances also show that the optimization of everyday patterns of behavior was not the only criterion used for the floor plan. In fact the floor plan was not derived from ideal functions, the shape of the site, or an imperative aesthetic vision, but from a found object. Any handyman knows all about making use of whatever happens to be available, which, in this case, was a pre-cut base for a spiral staircase—an elongated, irregular pentagon with all the characteristics of an offcut left over when a job has been done. Ever since the first models on a scale of 1:20, that shape has been the dominant element in the concept. Another consistent feature is the slanting open fire and chimney. A third is the way that the house is placed on a plinth, a reminder of its origins as a relatively temporary architectural structure on not entirely firm foundations. But let’s first return to the layout. The internal space is articulated by two free-standing, partial dividers: the very substantial open fire and a rhomboid-shaped section of wall intersecting the area. These elements separate and connect the three main areas of the house: entrance/bathroom/services, living and sleeping area, kitchen and dining area. At the same time these two concrete structures introduce a precise, linear axis into the irregularity of the actual footprint of the house. The wall and the fireplace face each other, although this is less apparent to the occupant of the space than it is to anyone viewing the floor plan. Unless you happen to be there, waking up in the morning, and your gaze first alights on the positively brutalist shape of the chimney breast and the fireplace opposite you—before you turn round to see the sunlight playing in the drapes or the view out into the trees. And it is when you are lying there in bed, contemplating the fireplace and the narrowing space with its glass walls, wooden floor, and wooden ceiling, that you have a particularly strong sense of being on a ship. Captain of the ship–but where is she bound for, hidden away here in the mountains? Later on, when you walk around the house and look upward at its narrow end, there seems to be another nautical motif, in the shape of a steam-ship funnel, housing the emissions channels from the open fire, completely clad in copper like the edge of the roof, the sill running along the lower edge of the window walls, and the reverse two-stepped base. Images of ships frequently crop up in modernist architecture. It seemed that humankind was setting out on some great voyage. Anchors aweigh!—even landlocked architecture had its sights firmly set on the vast expanses of the future and the promise of the horizon. In Ferienhaus T you only come across any such pictorial fragments of freedom in passing, and they are answered by reminders of distance, sometimes by an almost stubborn sense of staying put. This becomes all too clear when you draw back the drapes and the house fully reveals itself to be a bungalow with floor-to-ceiling windows filling all its sides. Entirely unlike its famous predecessors—such as Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House (1951)—there is no gradual mediation between inside and outside. On the contrary, the approximately eighty-centimeter plinth, the wide sill, and the numerous wooden supports around the inner perimeter clearly set the house apart from its surroundings. In fact the scenery outside the house looks more like a picture, some distance away from it, even–and all the more so—on the side where the sheer, bare rock of the mountainside comes to within two or three meters from the house. The same can be said for the opposite view, when the house is seen from a distance. In this case it is particularly the two-step plinth, which so strikingly retreats inward toward the ground, that separates the house from its surroundings and almost gives it the look of an alien body of some kind. And if you climb up the mountainside above the cliff face and look down to the house, this otherness becomes all the more striking: the house seems to occupy its space like a sculpture standing in a landscape—connected to it yet autonomous, too.

The concrete features in amongst the wood, fabrics, and views that characterize the interior seem like an echo of the paratactic coexistence of house and landscape. These elements are the epitome of sculptural forms and, in view of the way they cut into the space, one might well imagine they were leftovers from some much larger buildings and intended for very different purposes. At the same time they recall a language of forms that is often seen in Schütte’s architectural models and drawings—a language that seems to be a mixture of dry and monumental. The dryness may partly be a reflection of the everyday architecture he saw around him as he grew up in the 1950s and 60s, but it is also partly the outcome of a deliberately unartistic, pragmatic, do-it-yourself approach. Meanwhile the monumentality, in this almost perfunctory form, serves as a rhetorical means to heighten the evocative nature and drama of the stories his works are telling. In the concrete elements in Ferienhaus T this vocabulary takes on an almost sublimated form, embedded in the practical, private dwelling in this location. And yet, here too, one’s gaze constantly returns to the open fireplace–one of those rather uncanny openings that so often occur in Schütte’s building designs, not least in his Modell für ein Museum, which in fact appears to be an incinerator for works of art.

What kind of stay is possible—and appropriate—in this house? After all, that has to be an important consideration when someone like Schütte makes the transition from models to real architecture. The arrangement of the different functions in the house already makes it clear that it is not designed to facilitate a smooth-running, well organized daily round, but as a total experience. Of course, this is not to say that, for instance, the interlinking of bathroom, heating boiler, and cupboard in the narrowest section of the house is not efficient in the extreme. Yet for all the precision and elegance of the house’s architectural details, things are in a sense reduced to the bare necessities—sufficient for one person, or two at most. In order to preserve the simple generosity of the space, any equipment and furnishings have been kept to a minimum. A television would already be a step too far down the road of normalcy, as would a library. And in any case, this is not the place for rowdy, crowded parties. It seems that this house is better suited to a rather more elevated level of modest contentment; thoughts come to mind of an almost hermit-like, temporary self-reliance. The open fire as a quasi-mythical place of meditation conveys something of the right image. This underlying feeling, which is also present in the One Man Houses, takes a more open, so-to-speak more sociable form in Ferienhaus T. The sense of shutting out the world is stronger in the one-man hermitages, which are more like self-sufficient retreats, and their few pronounced openings seem like look-out positions for remote observation rather than for making contact with others. It is not by chance that they are described as houses for men, rather than for people in general (and certainly not women). Taking things to something of an extreme, they might even be described as generic portraits of the human condition for men today. However, in the case of the only One Man House that has been realized so far, these rigorous, even rather polemical features have been somewhat toned down. In fact it has turned into a garden pavilion, to which the owner can withdraw for a few hours at a time, and thus takes its place in the noble tradition of architectural follies designed to provide a little Somewhere Else in close contact with nature. For the owners of follies “actual usability” is more of a “notion” rather than a tried and tested reality, which in turn means that the finished house is in fact “impregnated with the conceptual quality of a model,” as Ulrich Loock has put it.

Ferienhaus T seems to go one stage further in that respect. It is not only sleeker and more pragmatic, it is also more communicative—without relinquishing its element of rather sophisticated restraint. The occupant’s latent awareness that, although he is in a real building, he is also a figure in a model, in an experimental set-up, is always present somewhere on the margins of his perceptions. Ferienhaus T is perhaps not so much architecture as we know it but rather an objet d’architecture, that is to say, while it owes its existence to the praxis of architectural construction, it is at one remove from that, for it is intended not only to be used but, importantly, also to be contemplated and considered. The sense that this structure is “impregnated” with the characteristics of a model perhaps ultimately arises from the occupant’s uncertainty as to what he should actually do here, since the notion of any distinct functionality seems to be of secondary importance. The rather random experiment of staying for any length of time in this house in fact has a lot in common with the hard-to-define nature of holidays. Creating space for other thoughts and attitudes by doing nothing? Or: a house where one is at leisure, in other words, a place of opportunity and free time, to do something, a house that is free of and open to . . .

If the “lake” in the sentence that precedes this essay (which is taken from a conversation with Thomas Schütte) is simply replaced by trees or rock, it could equally well apply to Ferienhaus T. The pictures that make a person feel bad and nervous could certainly be examples of contemporary art. The desire to occasionally escape from their “terror,” to take a holiday from the rumpus around them—this is not a need that could be described as a personal weakness that is best not talked about. “Necessity” here implies recognition of the whole person and the “end” an awareness of one’s responsibility as an artist. None of this has anything to do with the notion of an idyll, in the sense of a false, self-sedating consciousness. Nor is it a coy exaggeration, a red herring for those who encounter and enter these houses. In the same way that Schütte’s intense engagement with the human figure, particularly in the case of his Women, never sees him either succumbing to or merely playing with traditional role models, nor is it ever simply about his own state of mind, in Ferienhaus T there is also a strange, sublime form of resistance to accepting the status quo—for all the desired or therapeutic peace it exudes. This holiday home subliminally also contains within it that unsettling external world, with all its challenges and contradictions. However freely one’s gaze travels out into the surroundings or settles contentedly on the simpler of form of life in the interior with its almost dreamy colors, even in this realized model there is still something of its original waywardness. However firmly Ferienhaus T is anchored on this mountainside, it could equally well be somewhere else, it could be telling quite different stories to the one it is telling here. After a few days the occupant has to pack his bags, close the curtains again, lock the door, and leave, so that when the time comes the house will once again be in the position to greet one with sufficient distance—and with a new holiday story.

Translated from the German by Fiona Elliott

(Published in: Thomas Schütte - Ferienhaus T, ed. by Rafael and Teresa Jablonka, 2014, pp. 38-47 (German), pp. 48-57 (English))